A continuation from Part 2 of the journey through each series within the Barbara Mertz collection.

Subject Files I spent probably several hours total oscillating between “subject files” and “research files” as a series title for these materials. I finally settled on the former, as it was unclear if some of the materials were intended for research purposes versus personal or professional interest. For example, was the collection of Mystery Scene magazines’ purpose to keep abreast of the field, or did Mertz need them to research a particular topic? Because some of the subjects she researched for novels became personal interests (her interest in gardening stemmed in part from her research for Vanish with the Rose), the line was very blurred. Were the materials on clothing and textiles collected as reference sources for descriptions of historical clothing in her novels, or were they educational tools to help Mertz build her vintage clothing collection? Or both? It was fascinating to see her research process for her writings and try to connect materials to the books that they may have influenced, especially the paper dolls that spanned hundreds of years and a myriad of geographical locations.

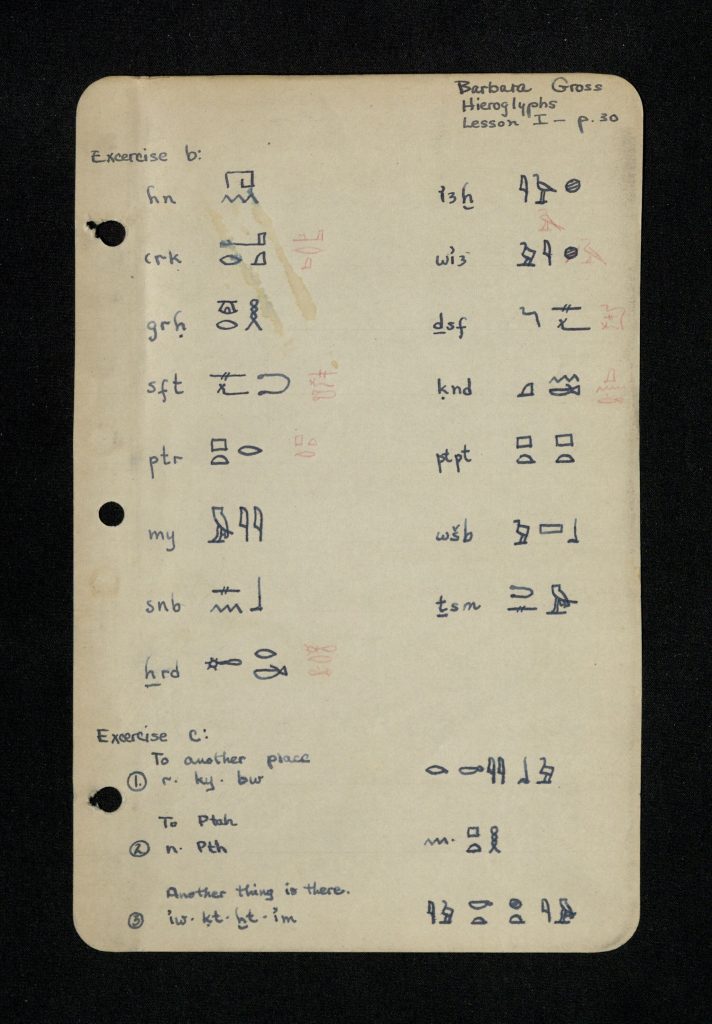

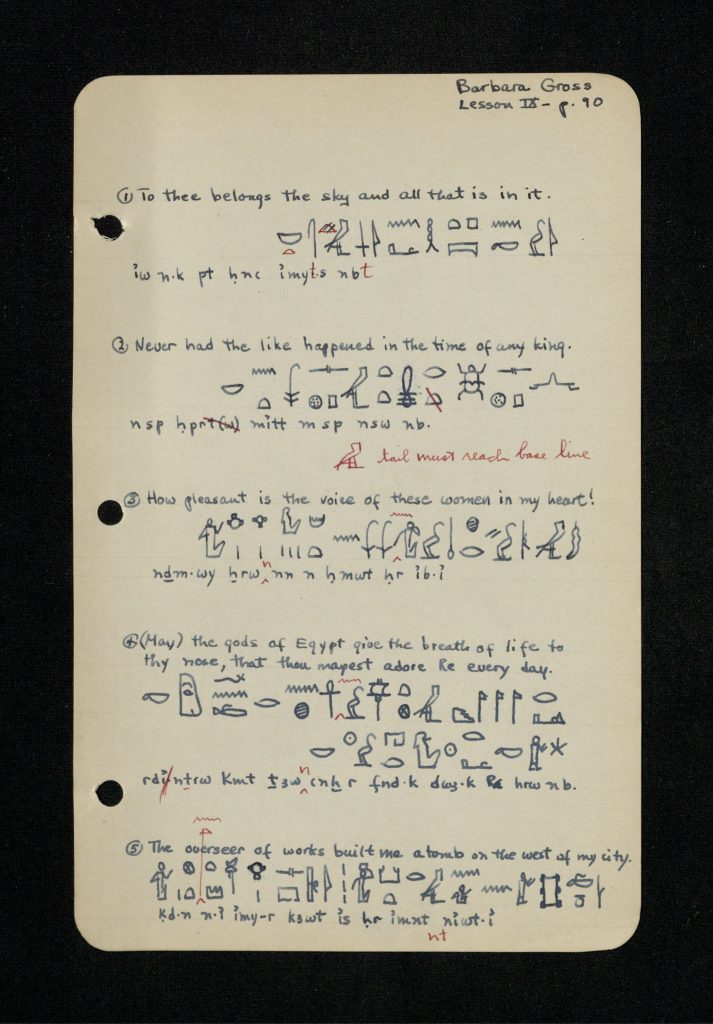

It was hard to pick a favorite item or folder in this series, as each subseries was so disparate, but Mertz’s Egyptology coursework was especially exciting, as I had no idea what went into the study in practice until I flipped through some of her textbooks and notes.

This is also the series in which the Corn Incident took place. In short, I opened a very full accordion file labeled “Germany” and removed a number of 1960’s travel guides and maps of Germany, after which a not insubstantial amount of dried corn poured out into my lap. I’m guessing this was an unintentional addition to the folder, as there was also some birdseed in the original box which seemed to indicate that it had been stored near foodstores for outdoor animals. I haven’t touched on the conservation aspect of archival processing much, as for the most part it consists of sending folded galleys and oversize posters to the conservation department for flattening and special enclosures, but sometimes strange and/or gross things do crop up. I once found a rat’s nest inside a box of papers; the rat had luckily vacated the premises before I got there. I’ve seen typescripts held together with ethernet cables, papers with circled and annotated stains of unknown source, and a “Lifetime Acheesement” award that may or may not have once had real cheese glued to it (only that last one is a Mertz collection item).

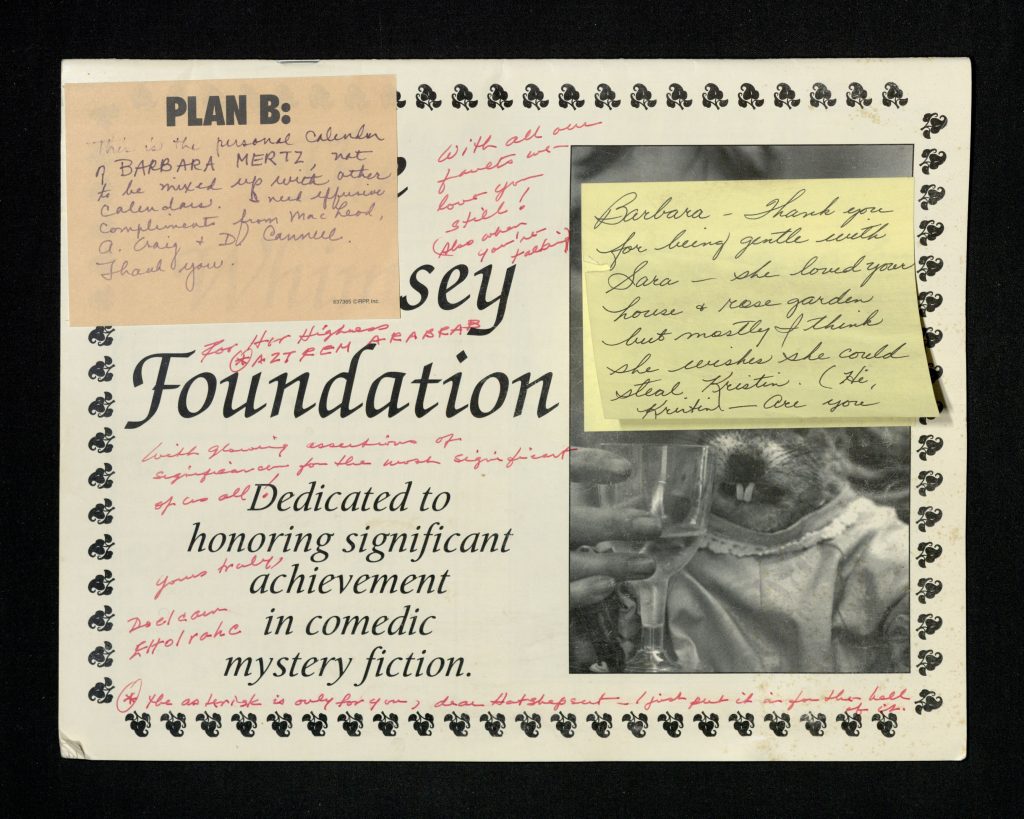

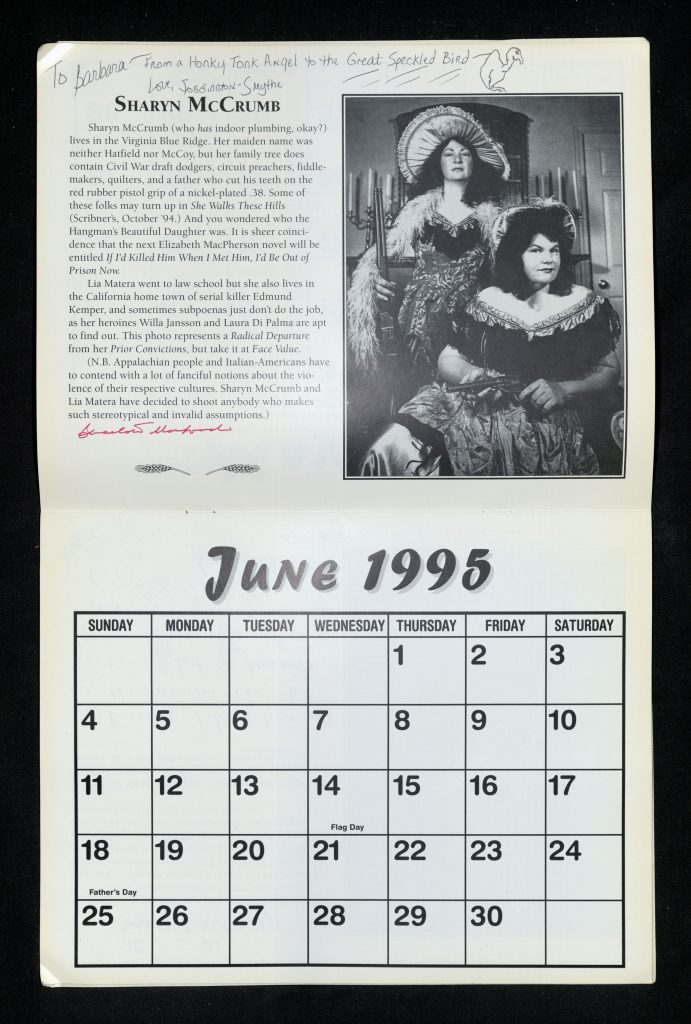

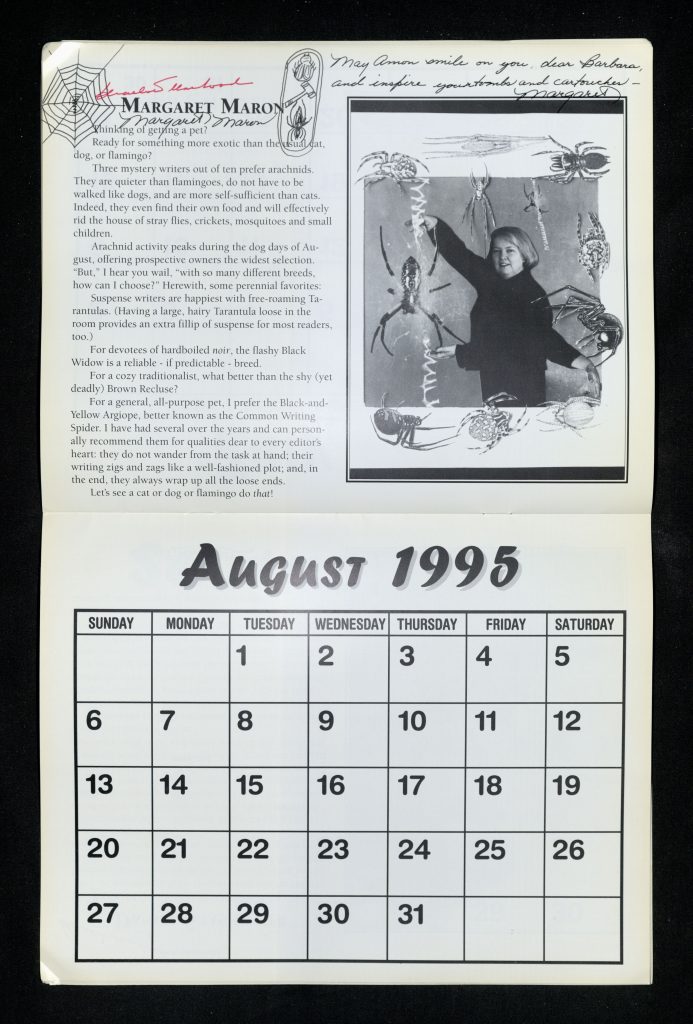

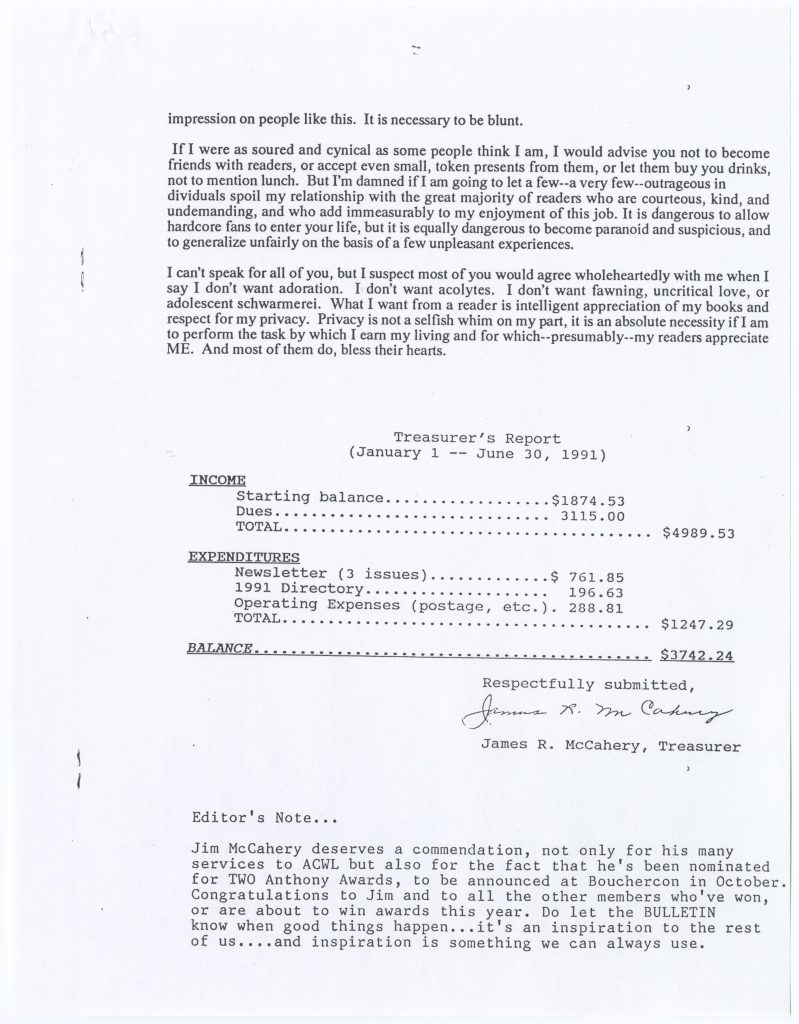

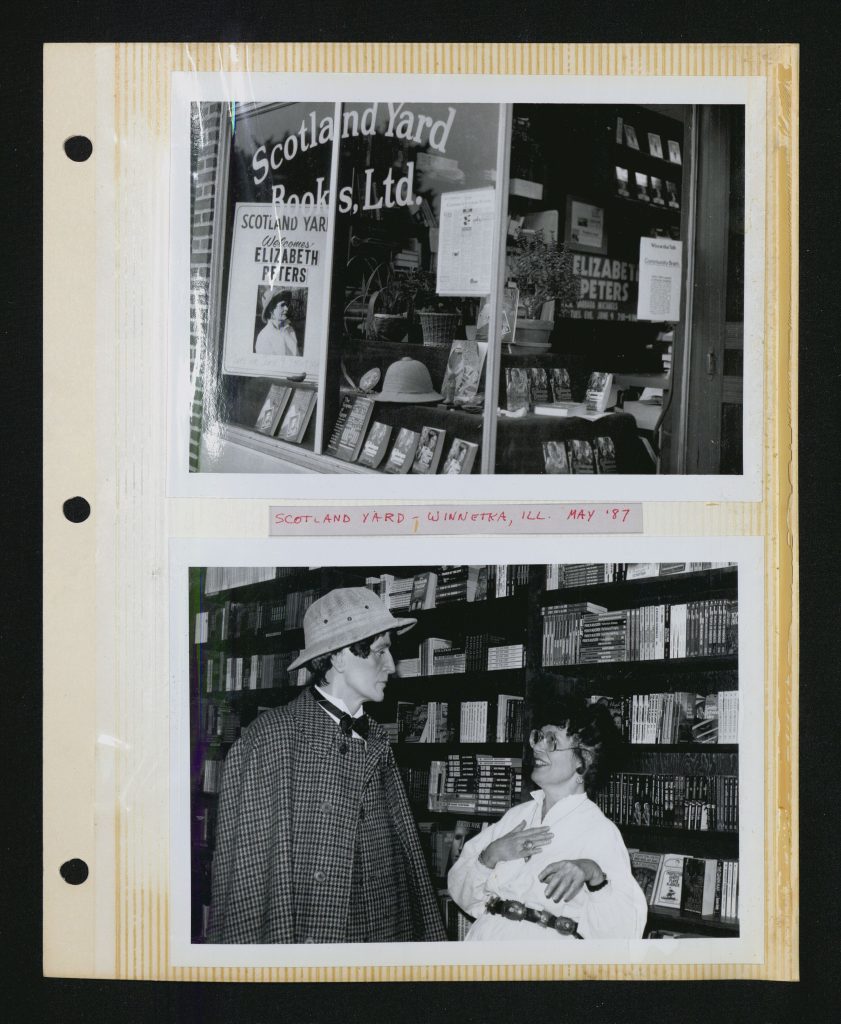

Professional Files This series may have taken the most up-front research to sort in a logical way, as it is riddled with acronyms and references to field-specific concepts, events, and people. The overlap in timelines and participants between Malice Domestic, Grouchercon, Sisters of Crime, and other mystery genre organizations and conventions that Mertz helped found made it difficult to tease out which documents related mainly to which organization/convention; this was compounded by Grouchercon having a (loosely followed) rule that members not speak of or acknowledge its existence. However, a very helpful series of posts on the “Remembering Barbara Mertz” blog helped straighten out some of these timelines, as well as provided an explanation for the photos of a stuffed muskrat in a dress that I kept seeing:

“Then there was the time when Hess, Sharyn McCrumb, Dorothy Cannell, and Margaret Maron decided to give out the W(h)imsey Award for comedy in mystery. (Lord Peter Wimsey is the hero of a series of mystery novels by Dorothy L. Sayers.) The award was a stuffed muskrat in a skirt and hat.” – “Memories of Malice (Part IV)”, author unknown

The materials in this series highlight both Mertz’s insistence on finding fun in everything she did as well as her constant professionalism and dedication to helping others in her fields. From creating a convention to highlight the cozy mysteries genre – an underrepresented subgenre in Mystery Writers of America, which she suspected was due to the majority of its authors being women – to serving as president of American Crime Writers League (ACWL) and helping writers fight for clearer royalties and better convention experiences, Mertz consistently gave back to her communities and attempted to use her own experiences to lift up fellow writers and Egyptologists.

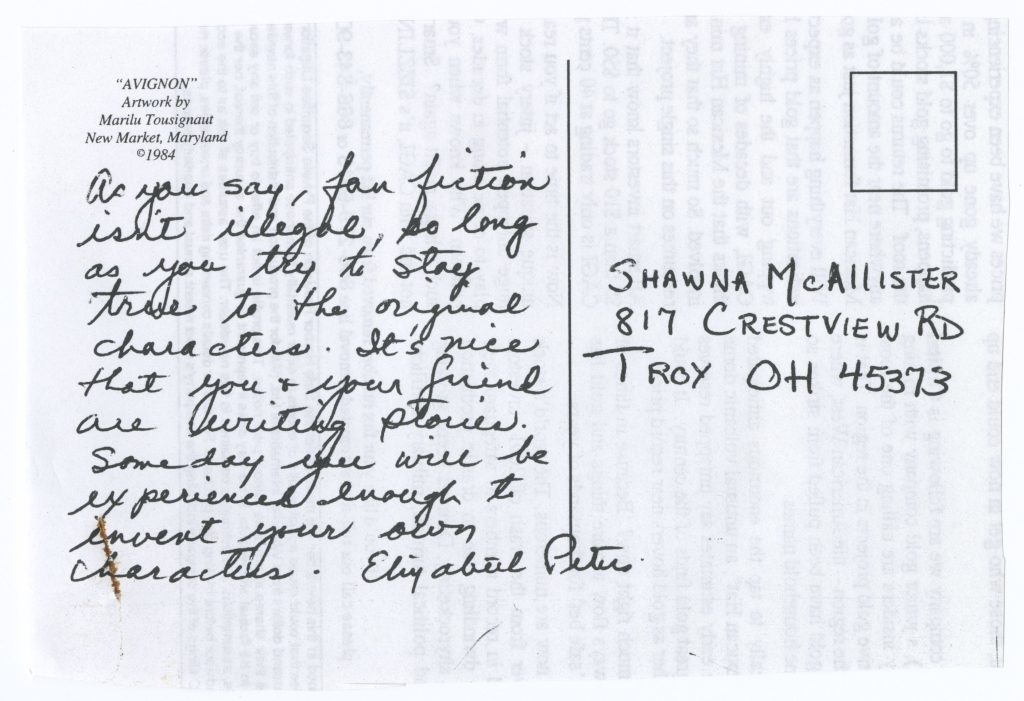

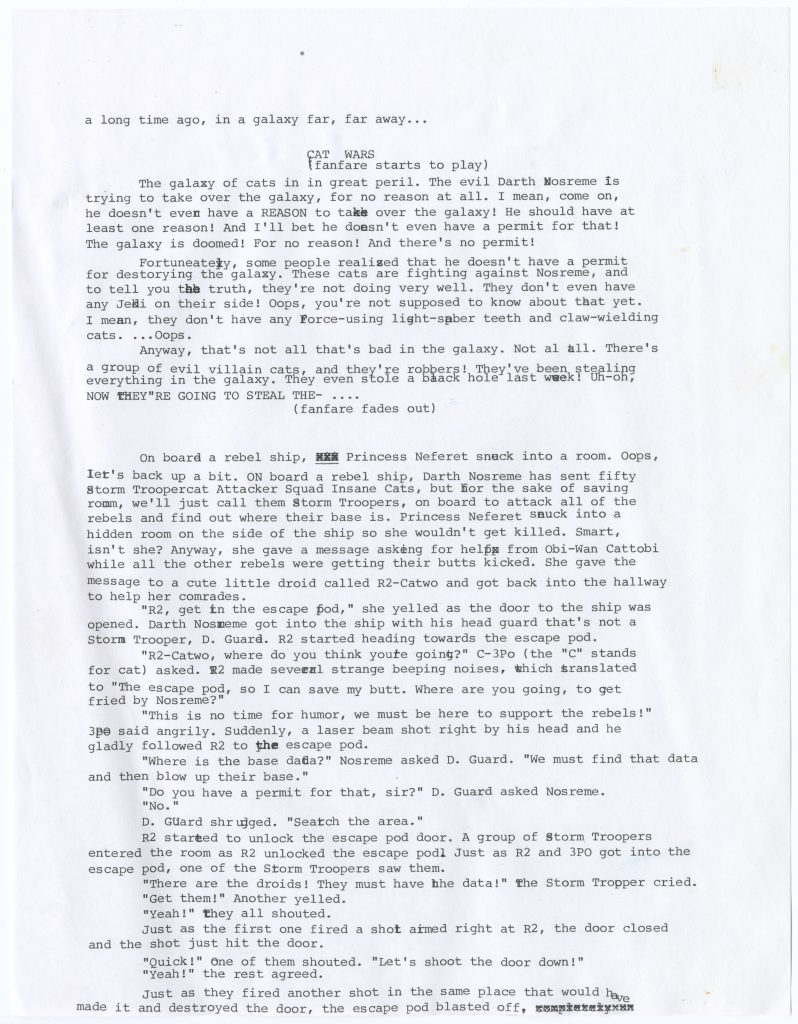

Writings by Others This series was born out of the number of writings people sent to Mertz as gifts or for her review, despite the fact that Mertz stopped giving blurbs due to her demanding schedule. Many of these typescripts and monographs were removed from the materials that ended up becoming the Correspondence series; my stipulations for doing so were that I kept the related correspondence with the writing, and that the writing must be a complete work rather than a single poem or extract. My favorite material in this series by far was the Amelia Peabody fanfiction sent to Mertz, both because I admired the bold move to send an author fanfiction of their own work and because it illustrated the deep impact her works had on its readers. On the advice of her publishers and agent, Mertz was unable to read fanfiction of her work for fear of subconsciously plagiarizing it in her own writing, but the fact that she kept it nonetheless seems to indicate that it was not entirely (hopefully) unwanted. One teen even wrote to get Mertz’s blessing for her Yuugioh!/Amelia Peabody crossover fanfiction, explaining the anime’s plot and offering her fanfiction.net penname in the process.

![: Letter from Shawna McAllister to Elizabeth Peters dated 2 August 2004 on pink-bordered stationery with the following handwritten text: “Dear Mrs. Peters, Please excuse the ugly pink stationery, I’m too lazy at the moment to write on unlined paper. I’m just writing to thank you again (and again, and again...) for writing (or organizing, at any rate) Amelia Peabody. My friends and I love Egypt, and your books give so much wonderful information without being textbook-y. [smiley face] Would I be bragging to say I’ve managed to get a lot of my friends as hooked on the books as I am? Whoops, yeah, probably. [smiley face] Your books are an addiction, I swear! But a good one. [smiley face] Fer instance, when I read the little article-let in Archaeology magazine a few months ago about Guardian getting released, my first thought was “Ahhh! New Peters-sama! Must get!” [smiley face] I sprinted for the library, and when I [arrow pointing right]”.](https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Shawna-letter-1-755x1024.jpg)

![Second page of letter from Shawna McAllister to Elizabeth Peters dated 2 August 2004 with the following handwritten text: “found it on the new release shelves I squealed and just about managed to get myself kicked out. [smiley face] Of course, once I started reading it, I had to dig a bout on my bookshelves at home until I found my dad’s old falling-apart-but-still-good paperback edition of Last Camel. That was in May, and I’m debating going back and reading them again, because that was right around the time I found out my beloved grandfather died, so my memories around that time are a tad smudged. But on to the point of this letter (besides rambling on like a fool). I’m real big into anime (that is, Japanese animation), especially a show called Yuugioh! (yeah, a teenager who loves a “kids” show. Please don’t get me started on that.) The main premise of the show is about the spirits of an Egyptian pharaoh (fictional) and a tomb robber who are reawakened in the modern day. My friend Katia and I came up with the idea of writing a story about what would happen if the tomb robber and the human boy who acts as “host” for his spirit got sent back in time and met up with the Emersons. [smiley face] No real plot yet, but we’ve [arrow pointing right]”.](https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Shawna-letter-2-754x1024.jpg)

![Third page of letter from Shawna McAllister to Elizabeth Peters dated 2 August 2004 on pink-bordered stationery with the following handwritten text: “got the vague idea that Sethos will pop up and steal some important artifact and Bakura (the tomb robber spirit) will “help” get it back, only to attempt to steal it for himself when they catch up with Sethos. Meh, not much yet, but we’re working on it. Anyway, sorry to bore you with a half-baked idea, but I just wanted to give you some idea of what we’d be doing with (or to?) your characters. Usually when we write fanfictions (stories of our own using copyrighted characters) we post them online at a website called fanfiction.net. Which is perfectly legal, I promise, since we don’t may any money off of it. But still, I wanted to make sure it was okay with you for Katia and [arrow pointing right]”.](https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Shawna-letter-3-754x1024.jpg)

![Fourth page of letter from Shawna McAllister to Elizabeth Peters dated 2 August 2004 with the following handwritten text: “I to do a fanfic using the Emersons. If not, we’ll probably still write it anyway, but it’ll just be for our own amusement, and we wouldn’t post it. [smiley face] Thanks for listening, and if I seem a tad incoherent, it may be because I have Celtic music blasting out of my stereo. [smiley face] Yeah, I’m a geek. Good luck with your next novel! Yours, Shawna McAllister // P.S. If for some remote reason you’re interested in what writing I’ve done, my penname on Fanfiction.Net is Wingleader Sora Jade [hyperlink to user page]. One of my stories, “Hot Sands, Warm Arms” was inspired by the Amelia Peabody books, and one of the characters, Malik by name, acts kinda like a young Ramses [smiley face]. Be afraid...”](https://blogs.libraries.indiana.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Shawna-letter-4-755x1024.jpg)

Personal It was difficult to separate out Mertz’s “personal” materials from what could also be considered professional, legal, correspondence, or research, all of which already had their own series. As with every choice in this and every archival collection, it was a subjective if justified decision that came down to what the material’s primary research value was in my opinion. For example, I put Grace Tragellas’ (Mertz’s mother’s) deeds in the Personal series despite the fact that they are legal documents and would fit within the scope of the Financial and Legal series because I anticipated their most significant research value being to provide biographical and personal background on Mertz, rather than providing financial or legal insight. I decided that Mertz’s high school yearbook belonged in the Personal series rather than with her other writings even though it features Mertz’s poetry because I felt it told more about her personal life than about her career, the latter of which was the main focus for the writings-based series in the collection.

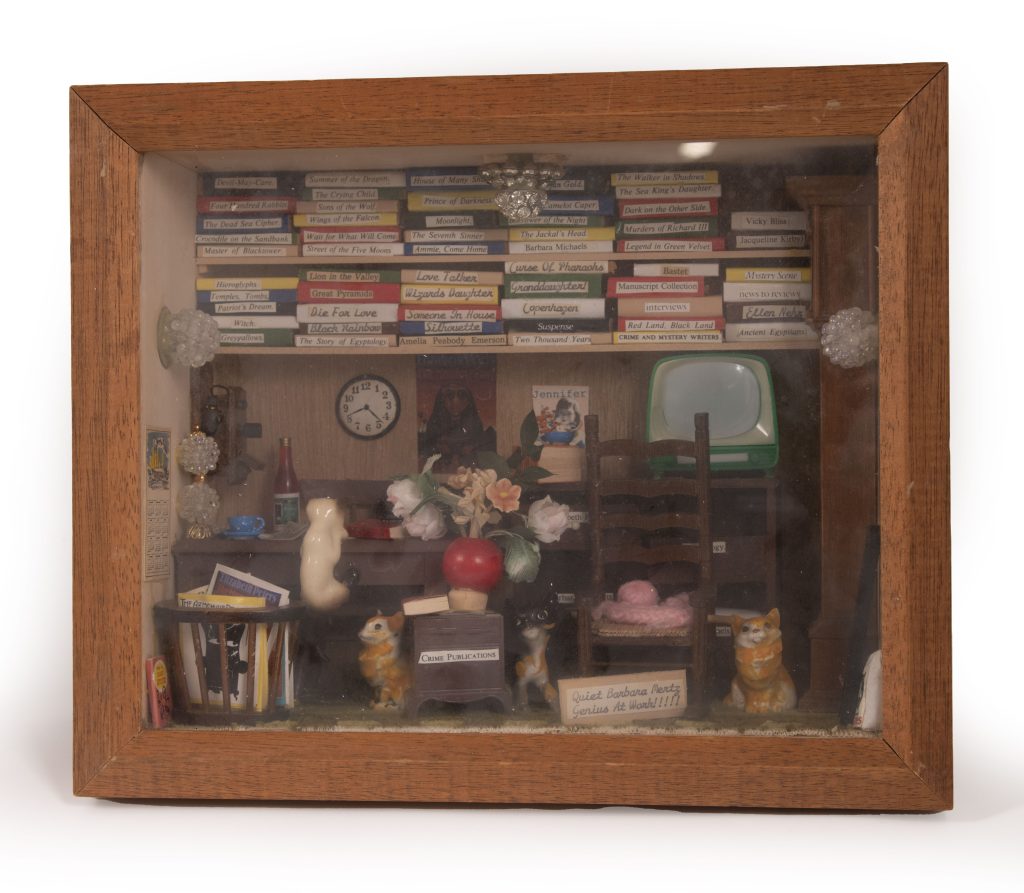

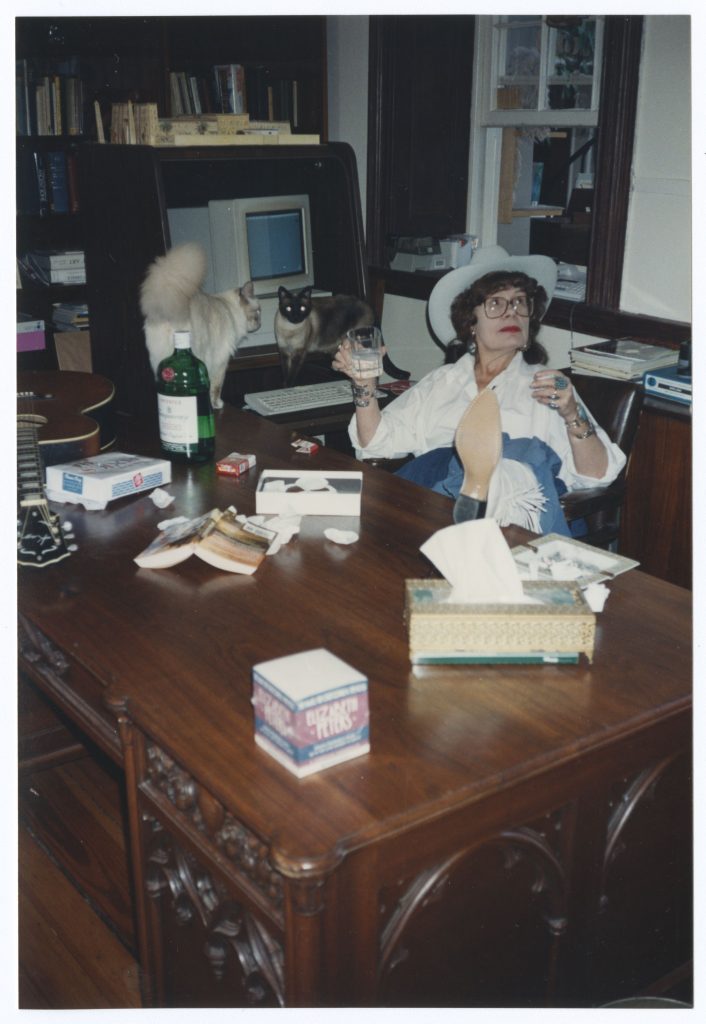

This series more than any other felt like a snapshot of a life, from the “Items from Barbara Happy Board in kitchen” folder that held photographs of friends and other ephemera presumably hung in Mertz’s kitchen to the two physical card catalogs of her personal library. These physical items represent a complex, well-lived life just as much as the birth certificate and memorials, offering insight into Mertz’s daily experience and interests. It can be difficult to remember the person behind the papers when processing a collection, either because of the creator’s immense success and impact or simply because the majority of daily archival work deals with papers as objects to sort rather than as representations of humanity, so the Personal series is often a very grounding reminder of the creator’s presence in the collection for me.

Photographs If there is a significant portion of photographs in a collection (for me, this constitutes more than one or two folders’ worth), I will often separate them and create a Photographs series because of the handling and use differences of this type of material. Photographs are some of the only types of items in an archival collection that require gloves to handle due to the ease of fingerprint and oil transference, so grouping them together physically can help accommodate the handling differences from other parts of the collection. In addition, negatives, slides, and other visual formats require special equipment to view, so keeping them together can (hopefully) save patrons and users time and labor.

It can be difficult to describe photographs given the lack of labels or captions for the most part, and it’s much harder to make assumptions on what an item is and how to describe it with photographs than, say, with typescripts or other materials that have set formats and context clues (titles, character names, etc.) as to their contents. Luckily, Mertz and Kristen Whitbread’s labeling and organization once again saved me a great deal of time and effort (thank you to everyone who labels and dates their photos on the back!). On the other end of the spectrum, I once processed a collection with several boxes’ worth of loose photographs, none of which had labels or any kind of organization; I ended up separating them by content (“creator and friends,” “friends and family,” “creator and wife,” etc.), which was effective but also required me to learn and recognize the face of the creator across 80-plus years of life (along with the faces of his many wives) in order to identify and properly sort each photograph. The main creator and subject of this collection also happened to be a nudist, which was both beneficial in giving me more features to compare and attempt to assign the photo a date range and disconcerting because of how many cumulative hours I probably spent looking at their genitals as part of my job.

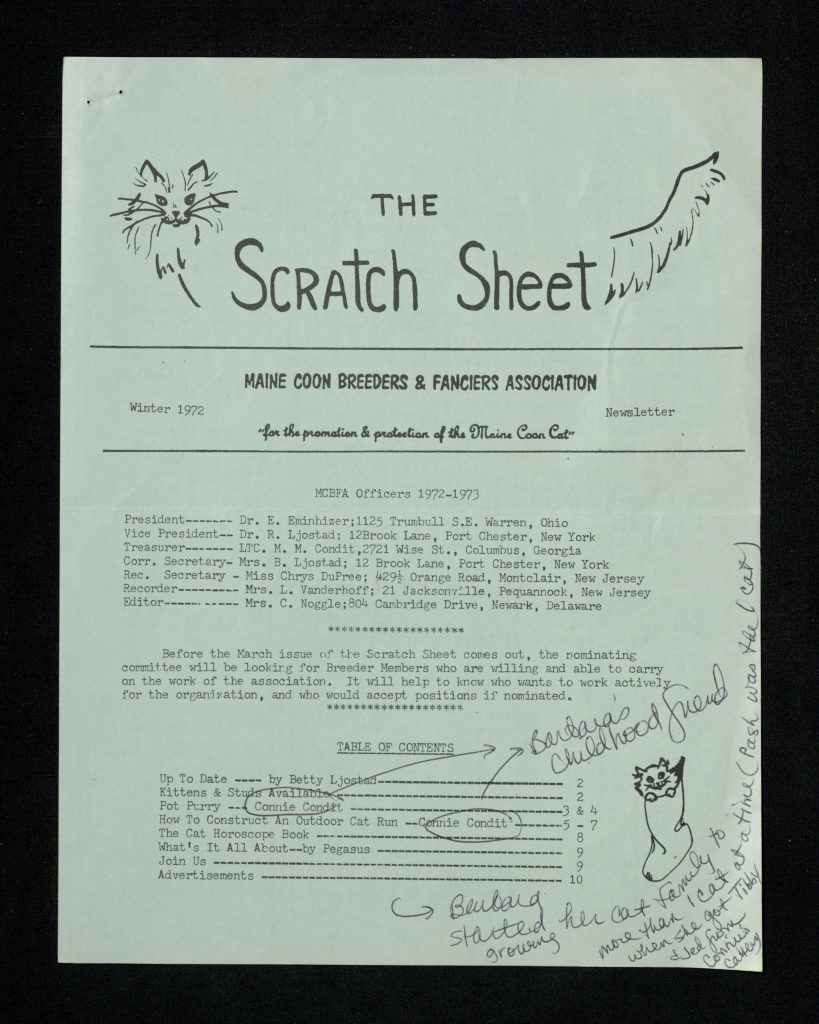

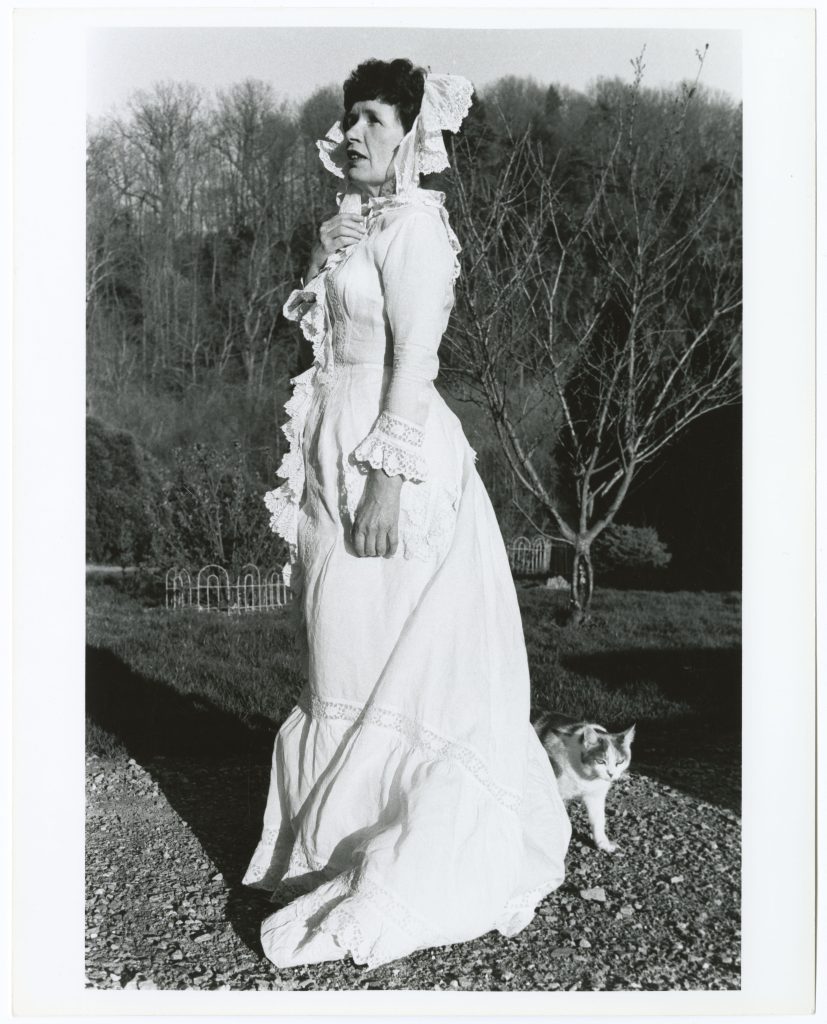

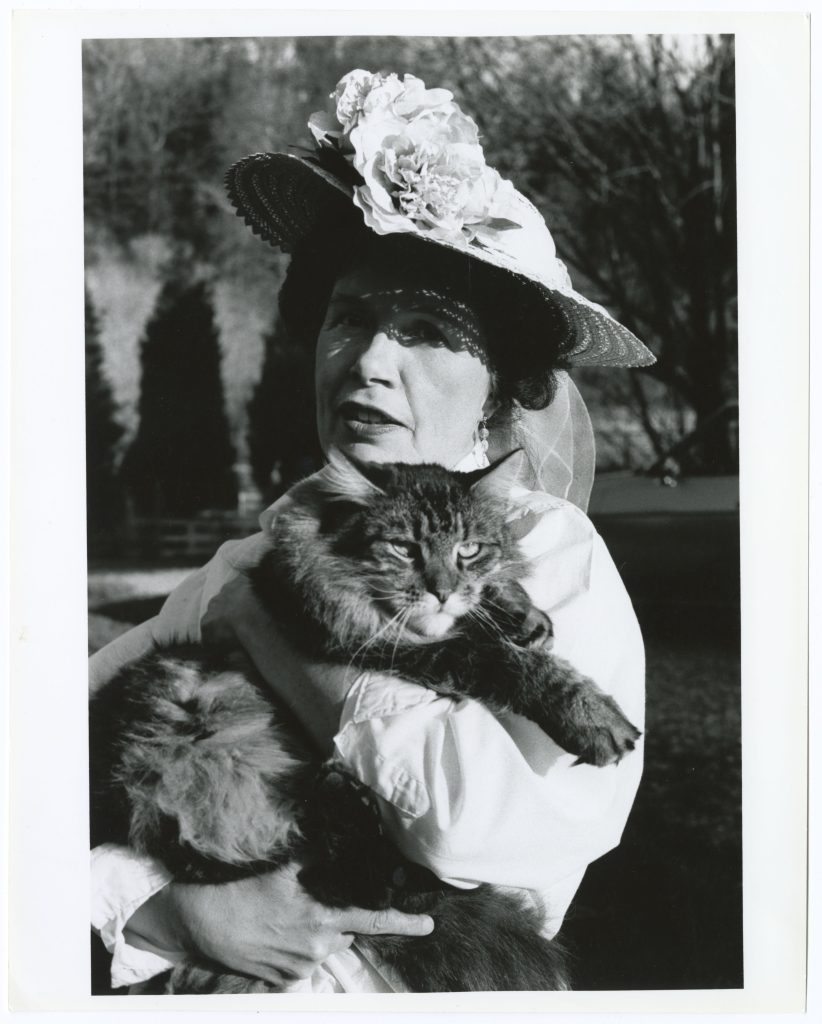

While it’s difficult to pick a favorite photo or album, the pet photos were definitely some of my favorites. This was another very humanizing set of materials – regardless of how talented and successful Mertz was, her cats still knocked things off ledges and got into mischief. These photos also helped to put faces to the names (and tufts of hair) I’d discovered throughout the collection.

1 Comment

Priceless! Thank you!