“I never really intended to be an archivist,” says Mike Mashon, after recounting his diverse educational background. Mashon, the Head of Moving Image Section at the Library of Congress, received his undergraduate degree in Microbiology from Louisiana State University, going on to pursue a Master’s in the same field at the University of Texas. Working for the Texas Department of Health, he was the first person the organization ever hired to conduct research on AIDS. Yet the longer he worked with science, the less he wanted to make it a career.

Mashon’s early involvement with what would eventually become the South by Southwest Festival, as well as his presence on the University of Texas Film Committee, rekindled his long-standing love of movies and television. Earning a Master’s in Radio/TV/Film at Texas, he obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Maryland in 1996, writing his thesis on the relationship between advertising agencies and television networks in the 1940s and 1950s. After serving as curator at the Library of American Broadcasting, he became Curator of Moving Images for the Library of Congress in 1998, a position he held until being named the Head of the Moving Image Section in 2005.

At the National Audio Visual Conservation Center (NAVCC), Mashon oversees the cataloging, processing, physical integrity, storage and preservation of film and video, also conducting personnel management and setting goals and budgets for the fiscal year. Mashon also attends National Film Preservation Board meetings, advising on which films will be added to the National Film Registry every year. Although administrative work encompasses the majority of his duties (Mashon jokes he is a “mid-level government bureaucrat”), he is especially interested in outreach and access initiatives, particularly when it comes to the NAVCC’s online presence.

Since little moving image content has been added to the Library’s web site in the past decade, Mashon is working to expand the NAVCC’s web presence by creating a blog and making videos about the organization’s workflows operations. He recently acquired an HD camera to start making informational videos about the preservation process at the NAVCC, following a film or tape through the entirety of the preservation process, with the finished product being the film itself available online. Mashon notes that one of the goals of the NAVCC is to provide outreach services not only to the local community but to members of the archival field as well – these informational videos would undoubtedly be an excellent resource for fellow archivists.

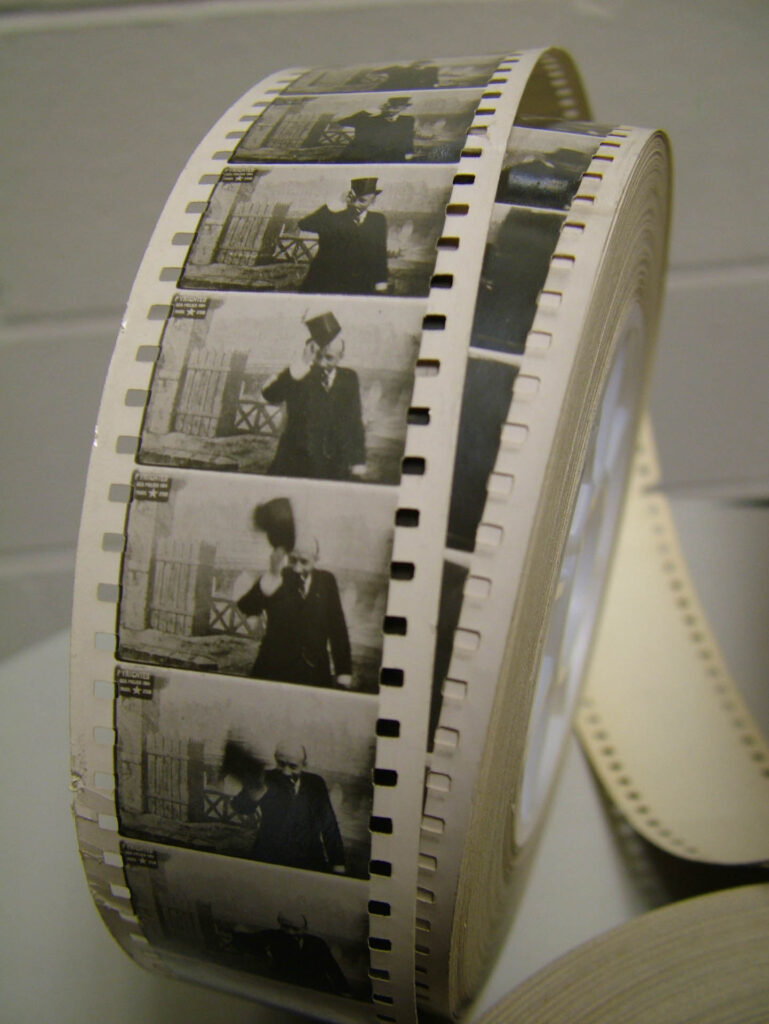

With the Library of Congress beginning to change its web architecture, it is becoming increasingly efficient to get moving image content on the web. Mashon spoke at length of the NAVCC’s more than 3,000 paper prints, which he deems “the crown jewel of our collection.” Paper prints were used to establish copyright in the early days of cinema, between the years 1894-1912, and Mashon notes “[you] can’t really write a meaningful history of American film without referring to the paper prints.” A number of the films in this collection have been transferred to other formats (16mm, 35mm), but only 500 of them – scans of 35mm reprints from the 1990s – are available online. Mashon notes that the only way a person would be able to view the remaining 2,500 prints in the collection would be to go to Washington D.C. – his goal is to eventually have the entirety of the collection scanned for access, using technologies such as the MWA Vario to scan 16mm negatives in real-time. Although the resulting files won’t be subjected to much digital cleanup other than speed correction, Mashon notes that the convenience of researchers not having to travel to D.C. makes this a worthy endeavor.

For those interested in film archiving work, Mashon advises that archivists starting out in the field need to be comfortable with digital technologies and metadata, as opportunities to use preservation experience skills will shrink over time. Many of the NAVCC technicians have degrees in library science rather than film preservation, emphasizing the importance of well-rounded skills. Mashon remarks that while the physical work of film preservation requires no small amount of skill, cataloging conistently proves to be an enormous challenge. Thus, a library science background will come in handy for the important task of information management.

Regarding the future of film preservation, Mashon remarks that he is slightly optimistic despite the inevitability of film stock production ceasing. He would like to see the creation of digital cinema packages at the NAVCC, noting that, while continuing to make prints would be ideal, only a handful of facilities would be able to screen these prints in the future. One example is that of significant film-print restorations the NAVCC has undertaken, for films such as Baby Face and All Quiet on the Western Front. While Mashon would like for audiences to be able to appreciate these films on the medium for which they were intended, he does not want to deny access to those facilities that may only be able to screen digital cinema packages. “If you’re not going to make it available to people as widely as possible – you’re just going to shut it away in a dark archive – there’s hardly any point in doing it,” he adds.

Mashon finds his work fulfilling, and he is quick to note the hard work undertaken by his employees at the NAVCC: “There’s nothing quite like being able to share the work of the Library of Congress with others. I’m always very humbled by that because I’m just representing the many wonderful people I work with who do the hands-on work.”

Perhaps most striking about Mashon is his passion about ensuring access for future generations of film lovers. “Film, television and radio are such powerful communicative media that we feel that is definitely worth our best effort to make sure that it’ll be preserved for those future generations.”

~Kaitlin Conner

1 Comment

I recall, in the early 1980s when I was a grad student at UCLA helping Bob Gitte at the film archive in the old Technicolor building, there was an older man working a strange Rube Goldberg contraption to slowly, frame by frame, copy old paper prints onto film. Was that part of the Library of Congress paper print collection?